Guest Post by Annika Weber, Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition and Trainee in the CSU InTERFEWS Program

An estimated 1.3 billion tons of food are discarded annually. At the same time there are over 2 billion people around the world experiencing hunger or lack access to nutritious and sufficient food1. Food waste refers to material that is safe and suitable for human and animal consumption, yet not consumed. The food waste and loss problems reveal inefficiencies in the food system that have consequential, permanent environmental impacts.

Food loss and waste threatens global food security and impacts people experiencing health, socioeconomic, and environmental disparities. This global problem of food waste is related to consumer behaviors (e.g., spoilage, discarded etc.), while food loss is typically defined in food supply chains as the edible material discarded during production and processing. Food production is also resource intensive, and the amount of wasted food on our planet is affecting humans, animals, and the environment.

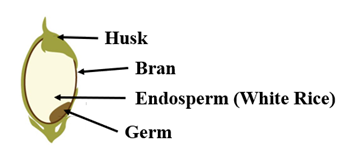

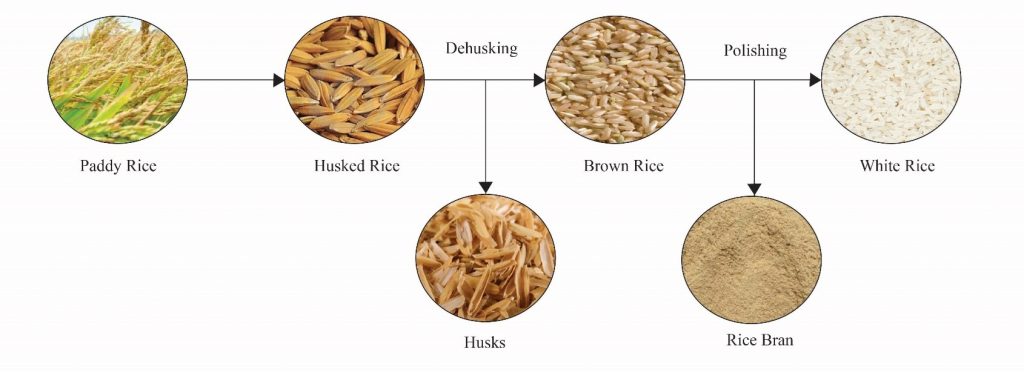

Rice is one example of a staple crop that contributes to global food loss, as more than 500 million tons of milled rice are produced each year, yet up to 40% of the rice grain yield is lost in the milling process as broken rice, husks, and the rice bran layer2. This is because white polished rice is primarily desired in the marketplace, and these white polished rice grains require removal of the fibrous husk and the nutrient rich bran.

During the rice milling process, the rice husk is first removed, leaving the bran layer on the rice grain, this is known as brown rice. Brown rice is then typically milled, or polished, to remove the bran layer, resulting in white rice. The byproducts in the rice milling process, especially the bran layer, or rice bran, contain certain bioactive compounds and nutrients. However, as most countries around the world prefer white rice to brown rice, more than 76 million tons of rice bran are produced annually, a majority of which is discarded, contributing to global food loss3.

As brown rice retains nutrients in the bran layer such as fiber, healthy fats, and vitamins, many developed countries refer to brown rice as ‘healthy rice’. With the amount of nutrient dense bran layer discarded as food loss, it might seem simple: eat brown rice instead. However, there are many logistic and cultural factors that make switching to brown rice not realistic. For one, brown rice does not have as long of a shelf life as white rice, and so is less desirable. This is due to the higher oil content in the bran layer, which is intact in brown rice, causing it to go rancid faster. Culturally, white rice is valued for its color, texture, taste, and many consider brown rice to be inferior. Also, as the demand for white rice is much higher, it is milled on a greater scale. This makes brown rice a more expensive product as different infrastructure is required, further contributing to its undesirableness.

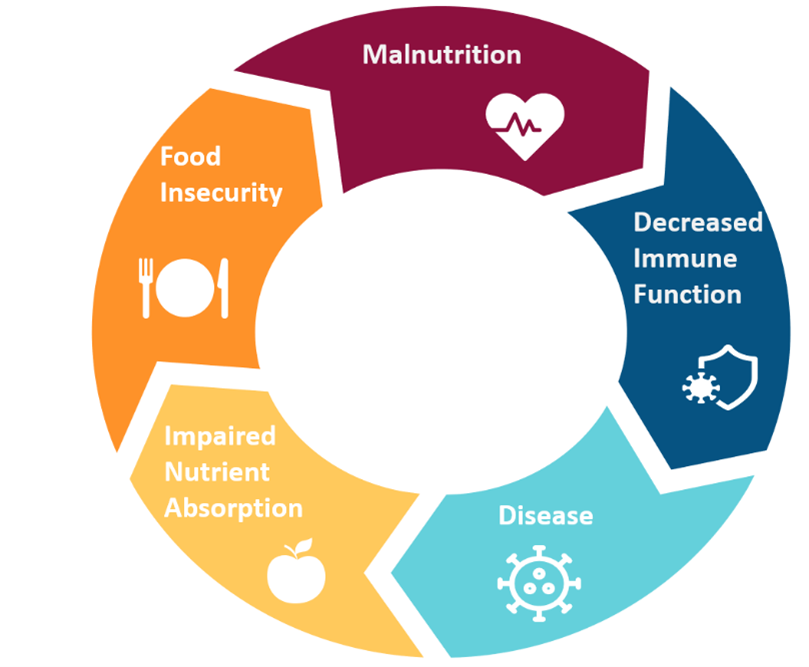

White rice is considered a refined grain, meaning it is low in fiber and nutrients. A growing area of research has found associations between refined carbohydrate diets, such as those high in white rice, and a greater risk for diseases such as diabetes. Also, as many of the world’s poorest countries rely on white rice as their main source of calories, they are not receiving many essential nutrients and have increased risk for malnutrition. As white rice is an essential staple for many countries that has deep cultural ties as well, simply switching to brown rice, is not a sustainable solution, and an alternative nutrient source is necessary.

Heat stabilized rice bran as a way forward to reduce food loss and improve health

One alternative that our CSU research lab and others have been testing is the inclusion of rice bran as a human food ingredient, as the addition of rice bran to already consumed dishes minimally changes texture and flavor profiles while increasing the nutrient density. This bran and germ fraction is rich in healthy fats, vitamins, fiber, as well as phytochemicals that makes it a nutrient dense food, and has even been referred to as a “superfood”.

In many rice producing countries, tons of rice bran are produced as a by-product that could be reincorporated as a co-product to provide a more nutritious meal. Research supports that rice bran helps prevent colorectal cancer, cardiovascular disease, and protects against pathogens such as salmonella and norovirus4-7. At the same time, weaning infants in developing countries consuming small amounts of rice bran had reduced diarrhea and improved growth8,9. The components of rice bran help strengthen vital systems such as the gut mucosal immune system and commensal microbiota. The existing and emerging evidence supports additional efforts to develop rice bran for human consumption, especially in regions experiencing malnutrition.

Challenges and barriers to rice bran adoption in the community

There are a few challenges that must be addressed for the implementation of rice bran as a human food ingredient and have prevented rice bran from already taking off. First, rice bran is not commonly consumed and there are various perceptions around consumption of this by-product. So far, our lab has focused on implementing rice bran as a food ingredient, meaning it can be mixed into already consumed foods. Rice bran minimally changes textures and flavors of already consumed dishes and has been well accepted in previous studies10. However, demands for brown rice and bran are mainly by health-conscious people in developed countries, and those in developing countries are often unaware of these foods and their health benefits11,12. For most of the population, food decisions are driven by cost, convenience, and preference especially as meals are often shared with entire families. Increasing available knowledge of the health benefits of rice bran will be beneficial to tap into this underutilized food ingredient.

Another challenge that must be tackled in marketing rice bran for human consumption is heat stabilization technologies. For the same reason that brown rice has a shorter shelf life, rice bran has a higher oil profile, meaning it will go rancid without heat stabilization. This process involves heating the bran under high pressure to reduce moisture content and dry the bran. This can be a challenge in low-resource areas of the world that may have access to rice bran but may not have heat stabilizing resources. Current developments in heat stabilization technology are expanding to appeal to these areas such as microwave and dry heating13.

Food safety considerations, such as awareness of mycotoxins and heavy metals including arsenic, lead and cadmium are needed. In some parts of the world such as parts of Bangladesh, arsenic contamination is an ongoing issue, as it has seeped into the drinking water and agriculture. In areas such as this with high risk of arsenic contamination, consumption of rice products should be limited.

Summary

Developing rice bran as a food source is one practical idea that could help meet immediate nutritional needs, while preventing food waste. Also, rice bran food system reincorporation requires no additional land use nor water input, and its development could help promote global food security while preventing food waste. Rice bran for human consumption addresses the problems faced in food and water insecurity, particularly in remote regions with little resources and high rates of malnutrition. The application of the food-energy-water nexus to this rice bran development project is intended to help preserve our essential resources, while also addressing global health challenges.

References

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, Rome, 2020).

- Bodie, A. R., Micciche, A. C., Atungulu, G. G., Rothrock, M. J. & Ricke, S. C. Current Trends of Rice Milling Byproducts for Agricultural Applications and Alternative Food Production Systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 3, doi:10.3389/fsufs.2019.00047 (2019).

- Zhuang, X., Yin, T., Han, W. & Zhang, X. in Rice Bran and Rice Bran Oil (eds Ling-Zhi Cheong & Xuebing Xu) 247-270 (AOCS Press, 2019).

- Kumar, A. et al. Dietary rice bran promotes resistance to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colonization in mice. BMC Microbiol 12, 71, doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-71 (2012).

- Henderson, A. J. et al. Chemopreventive Properties of Dietary Rice Bran: Current Status and Future Prospects. Advances in Nutrition 3, 643-653, doi:10.3945/an.112.002303 (2012).

- Lei, S. et al. High Protective Efficacy of Probiotics and Rice Bran against Human Norovirus Infection and Diarrhea in Gnotobiotic Pigs. Frontiers in Microbiology 7, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01699 (2016).

- Li, K. J., Borresen, E. C., Jenkins-Puccetti, N., Luckasen, G. & Ryan, E. P. Navy Bean and Rice Bran Intake Alters the Plasma Metabolome of Children at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Front Nutr 4, 71, doi:10.3389/fnut.2017.00071 (2017).

- Zambrana, L. E. et al. Daily Rice Bran Consumption for Six Months Influences Serum Glucagon-Like Peptide-2 And Metabolite Profiles Without Differences in Trace Elements and Heavy Metals in Weaning Nicaraguan Infants At 12 Months of Age. Current Developments in Nutrition, doi:10.1093/cdn/nzab101 (2021).

- Zambrana, L. E. et al. Rice bran supplementation modulates growth, microbiota and metabolome in weaning infants: a clinical trial in Nicaragua and Mali. Scientific Reports 9, 13919, doi:10.1038/s41598-019-50344-4 (2019).

- Leach, H. J. et al. Feasibility of Beans/Bran Enriching Nutritional Eating For Intestinal Health & Cancer Including Activity for Longevity: A Pilot Trial to Improve Healthy Lifestyles among Individuals at High Risk for Colorectal Cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 19, 1534735420967101, doi:10.1177/1534735420967101 (2020).

- Muhihi, A. J. et al. Perceptions, Facilitators, and Barriers to Consumption of Whole Grain Staple Foods among Overweight and Obese Tanzanian Adults: A Focus Group Study. ISRN Public Health 2012, 1-7, doi:10.5402/2012/790602 (2012).

- Kumar, S. et al. Perceptions about varieties of brown rice: a qualitative study from Southern India. J Am Diet Assoc 111, 1517-1522, doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.07.002 (2011).

- Spaggiari, M., Dall’Asta, C., Galaverna, G. & del Castillo Bilbao, M. D. Rice Bran By-Product: From Valorization Strategies to Nutritional Perspectives. Foods 10, 85 (2021).